Paul Graham, A1: The Great North Road

http://www.paulgrahamarchive.com/a1.html

From the publisher:

Photographer Paul Graham spent two years completing this documentary on the life and landscape of the Great North Road. Throughout 1981 and 1982 he made numerous trips along the A1, crossing and recrossing the length of the nation to record every aspect of life at the verge of this great road. The photographs reproduced in this book build not only into a significant documentary of the A1, but also provide a thread along which we can travel the Great North Road, deep into the nation’s heart, and weave a picture of England in the 1980s.

Stephen Shore, American Surfaces

http://stephenshore.net/photographs/seven/index.php?page=1&menu=photographs

From the publisher:

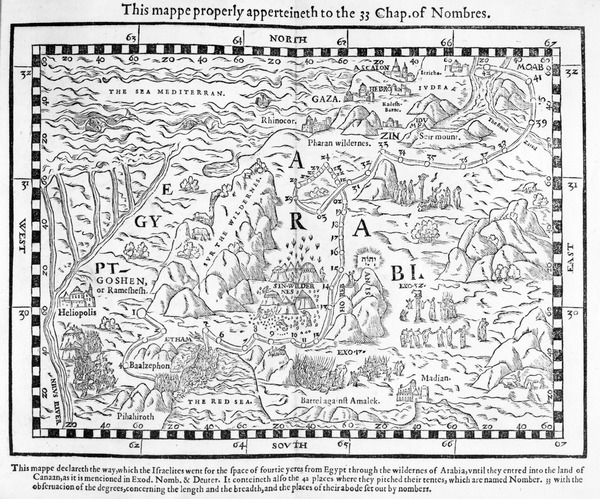

In 1972, Stephen Shore left New York City and set out with a friend to Amarillo, Texas. He didn't drive, so his first view of America was framed by the passenger's window frame. He was taken aback by the fact that his experience of life as a New Yorker had very little in common with the character and aspirations of Middle America. Later that year he set out again, this time on his own, with just a driver's licence and a Rollei 35 - a point-and-shoot camera - to explore the country through the eyes of an everyday tourist.

The project was entitled American Surfaces, in reference to the superficial nature of his brief encounters with places and people, and the underlying character of the images that he hoped to capture. Shore photographed relentlessly and returned to New York triumphant, with hundreds of rolls of film spilling from his bags. In order to remain faithful to the conceptual foundations of the project, he followed the lead of most tourists of the time and sent his film to be developed and printed in Kodak's labs in New Jersey.

The result was hundreds and hundreds of exquisitely composed colour pictures, that became the benchmark for documenting our fast-living, consumer-orientated world. The corpus of his work - following on from Walker Evans' and Robert Frank's epic experiences of crossing America - influenced photographers such as Martin Parr and Bernd & Hilla Becher, who in turn introduced a new generation of students to Shore's work.

Alec Soth, Sleeping by the Mississippi

http://alecsoth.com/photography/?page_id=14

From the publisher:

Evolving from a series of road trips along the Mississippi River, Alec Soth's "Sleeping by the Mississippi" captures America's iconic yet oft-neglected "third coast". Soth's richly descriptive, large-format color photographs present an eclectic mix of individuals, landscapes, and interiors. Sensuous in detail and raw in subject, "Sleeping by the Mississippi" elicits a consistent mood of loneliness, longing, and reverie. "In the book's 46 ruthlessly edited pictures," writes Anne Wilkes Tucker, "Soth alludes to illness, procreation, race, crime, learning, art, music, death, religion, redemption, politics, and cheap sex." Like Robert Frank's classic "The Americans", "Sleeping by the Mississippi" merges a documentary style with poetic sensibility. The Mississippi is less the subject of the book than its organizing structure. Not bound by a rigid concept or ideology, the series is created out of a quintessentially American spirit of wanderlust.

Robert Frank, The Americans

https://steidl.de/Artists/Robert-Frank-1013194243.html

From the publisher:

First published in France in 1958, then in the United States in 1959, Robert Frank’s The Americans changed the course of twentieth-century photography. In eighty-three photographs, Frank looked beneath the surface of American life to reveal a people plagued by racism, ill-served by their politicians, and rendered numb by a rapidly expanding culture of consumption. Yet he also found novel areas of beauty in simple, overlooked corners of American life. And it was not just Frank’s subject matter—cars, jukeboxes, and even the road itself—that redefined the icons of America; it was also his seemingly intuitive, immediate, off-kilter style, as well as his method of brilliantly linking his photographs together thematically, conceptually, formally, and linguistically, that made The Americans so innovative. More of an ode or a poem than a literal document, the book is as powerful and provocative today as it was fifty-six years ago.

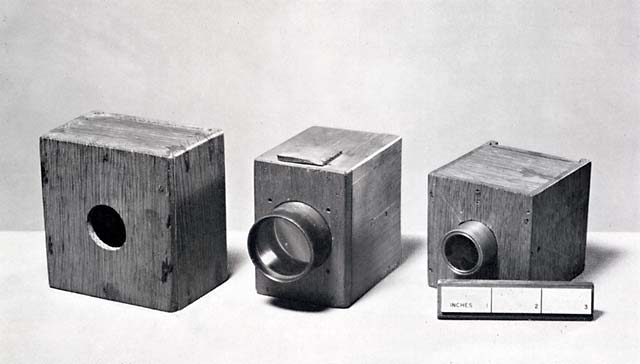

Kevin McElvaney, #Refugeecameras

http://kevin-mcelvaney.com/refugeecameras/

Photographer Kevin McElvaney gave refugees cameras in Izmir, Lesbos, Athens and Idomeni. Of the 15 cameras he distributed, seven were returned and McElvaney displayed the resulting images on his website. The goal for the project was to ensure that refugees were able to describe their trip from their own perspective, rather than from the viewpoint of an outsider who did not share the experience. I found this a very compelling series and wondered how different our documentary and news narratives would look if they were told from within rather than from without.

24 Photography

http://www.24photography.org/about/

This project is organized around a rule of “24 hours. 24 photographers. 24 images. 24 years.” Starting in 2004, a collective of 24 then-student photographers documented the first 24 hours of each New Year in multiple locations—in other words, a documented journey through both time and space. Although many of the photographs are taken in the UK a substantial number are not, and the organisation of the project demonstrates that while we share a common calendar there are many other things that we do not share. It is a fascinating visual trip to work through the years and see the points of convergence and divergence.

![Train Window - Green Pine{车窗-青松]. Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚2010](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5224bdefe4b0f7b35c282f4d/1488939247018-YFOP2WCTXKYP4TKMJGKY/55e1ef71-eacf-4603-88f0-e75da8552b87_l.jpg)