Postmodernism

In art, postmodernism was specifically a reaction against modernism. (Actually, I believe this holds true across the board. The hint is in the name.) The end of confidence in overarching meta-narratives or universal truths and the recognition of the importance of context and many small narratives, no one of which had claim to be “the truth.” Suspicion of the sufficiency of reason (it can’t be a complete suspicion of reason or there would be little point in pursuing postmodernist thought at all).

“Postmodern art drew on philosophy of the mid to late twentieth century, and advocated that individual experience and interpretation of our experience was more concrete than abstract principles. While the modernists championed clarity and simplicity; postmodernism embraced complex and often contradictory layers of meaning.”

With the end of ‘authority’ came an assertion of complete freedom that had expression in rule-breaking, self-awareness, parody, appropriation and ironic commentary.

- Pop art: no separation between fine art and popular culture

Conceptual art: concept more important than the created performance or artefact (personal interpretation and experience)

Feminist theory and art: lived experience of women (article only mentions feminist theory, but there is a range of localized theories/experiences: queer theory, post-colonial, etc.)

Neo-expressionism: re-birth of myth, symbol and history (rich in interpretive possibilities?)

Appropriation and other borrowings: drawing on other cultural products as nothing is normative

Performance art: accessible and often transgressive of established norms and narratives

Representation

Hall, S., Evans, J. & Nixon, S. 2013, Representation, Second ed, The Open University, Milton Keynes. (particularly Chapter One: ‘The Work of Representation’).

“Representation connects meaning and language to culture. [...] ‘Representation means using language to say something meaningful about, or to represent, the world meaningfully to other people.’” (p.15)

Three theories of representation—reflective (language reflects reality), intentional (language expresses the intent of the communicator) and and constructionist (language is a social construct using agreed-upon and arbitrary systems of codes to express and interpret meaning)—and within the the constructionist approach there are a further two: semiotic and discursive.

Representation as "standing in place of" (describe or depict) or "standing for" (symbolize). Words stand for or represent concepts. (p.16)

"Representation" is the production of the meaning of the concepts in our minds through language and consists of a system of concepts of things in our heads that we perceive or of more abstract concepts. (p.17)

A system of representation “consists, not of individual concepts, but of different ways of organizing, clustering, arranging and classifying concepts, and of establishing complex relationships between them.” (p.17)

We are able to communicate “because we share broadly the same conceptual maps… [and] ‘belong to the same culture’.” (p.18) We must also share a common language.

Signs are “words, sounds or images which carry meaning”. Signs are, in turn, organized into languages, of which there are many varieties.

Signs have to be interpreted. (p.19)

“Codes fix the relationships between concepts and signs. They stabilize meaning within different languages and cultures.” (p.21)

Reflective approach to representation: meaning lies “in the object, person, idea or event in the real world, and language functions like a mirror, to reflect the true meaning as it already exists in the world.” (p.24)

Intentional approach to representation: “words mean what the author intends they should mean.” A difficulty with this approach is that no author is the sole arbiter of meanings, since language is shared.

Instead, meaning is constructed through representational systems of concepts and signs.

“Meaning is produced within language, in and through various representational systems which, for convenience, we call ‘languages’, (p.28)

Saussure distinguished between a form, which he called the signifier, and the corresponding concept that it brings to our imaginations: the signified. Together and arbitrarily, they are a sign. (p.31)

“Signs [...] ‘are members of a system and are defined in relations to the other members of that system.’” (p.31)

Much of meaning is derived from difference. Difference can have ranges and degrees, and need not be strictly binary.

“It is the differences between signifiers which signify.” And the relations between signifier and signified vary with time, as products of history and culture. These changes lead to new meanings and point out the importance of interpretation. (p.32)

Saussure further distinguished langue (a language system) and parole (any specific communication. (p.33)

Saussure concentrated primarily on the relation of signifier and signified, paying relatively little attention to reference, those things in the real world to which language refers. (p.34)

Saussure’s work also concentrated on how language works internally (its formal aspects) rather than on its actual use. His thinking was discounted as a ‘scientific’ system but found continued usefulness as a means to examine meaning and culture. The limits of his system also pointed out the degree to which languages, although rule-bound, evolve. The systems of rules are not static. (p.35)

Saussure’s work was developed further in cultural studies by Roland Barthes and in anthropology by Claude Lévi-Strauss. (pp.36-37) Each field of meaning can be said to have its own langue and parole, with its own set of meanings created by constructed relationships between signifiers and signifieds. The work of identifying these systems and interpreting them is ongoing.

Foucault continued to develop such structuralism into discursive analysis: the study of “the production of knowledge through language.” (p.44) Any discourse is “true [...] only within a specific historical context.” (p.46)

Interpretation

Terry Barrett , Art Education, Vol. 47, No. 5, Interpretation. (Sep., 1994), pp. 8-13.

In this article Barrett offers a series of principles related to the interpretation of art. He describes three specific steps in viewing a work: description, interpretation and judgement. The first two lead to ‘understanding,’ which may make judgement ‘superfluous.’

Barrett’s principles are as follows:

- Artworks have ‘aboutness’ and demand interpretation. Barrett asserts several things here that he doesn’t develop or explain (although the responses are no doubt in the extensive references that he provides). For example, he dismisses the idea of some that art just ‘is’ and cannot be discussed. Instead, he moves beyond a work’s ‘is-ness,’ saying that ‘a work of art is an expressive object made by a person… it is always about something”. I think this is probably a fair point, because even if an artist created a work that was about ‘nothing,’ an idea of creating a pointless object (pure freedom? a statement about the ultimate meaninglessness of reality or our inability to communicate ‘reality’?) would still lie behind the creation of the work. I have a feeling that a geologist, an earth scientist or a biologist (or theologian!) might dispute the idea that trees and rocks do not call for interpretations, but he is making a point about the intent of the artist. Barrett claims that if something is created by a person, another person not only has the opportunity to interpret it, but the work itself asks to be interpreted. (This shows a confidence in the sufficiency of human reason, something that can’t be taken for granted among all commentators.)

Responsible interpretations present the artwork in its best rather than in its weakest light. I’m not sure why this automatically makes an interpretation more ‘responsible,’ but I agree that interpreters are well-advised to show generosity and humility in their work. Why bother with the work of interpreting if there is nothing to be learned from something another human made?

Interpretations are arguments. This statement leads to the helpful warning that we should be alert to the premises of a critic’s interpretation before accepting his or her conclusions.

Interpretations are persuasive. I expect that this is true most of the time, but I can imagine that a critic might review a work without necessarily trying to win the reader to a particular point of view: the critic’s goals could be educational (did you see this aspect? did you notice this possibility?) without trying to arrive at a particular fixed interpretation.

Some interpretations are better than others. Yes. A well-formed, experienced and reliable guide of good will deserves more of a hearing. And the ‘that’s just your opinion’ school of thought does indeed show up in the humanities and social sciences.

No single interpretation is exhaustive of the meaning of an artwork and there can be different, competing, and contradictory interpretations of the same artwork. Certainly—variety of context and viewpoint make a final interpretation of an artwork impossible. And this does not undermine the previous point about some interpretations being better than others.

Interpretations imply a world view. No argument here: this is the source of the context and viewpoint referred to in the previous point.

Good interpretations of art tell more about the artwork than they tell about the interpreter. Barrett sums up his point well in this line: “All interpretations reveal the critic, but the critic’s primary challenge is to direct the reader to perceive and understand the art object in question.” I accept this, but I’m not sure that a hardcore postmodernist would.

Interpretations are not so much absolutely right, but more or less reasonable, convincing, enlightening, and informative. From everything Barrett has said to this point in the article, this is a logical position to take.

Good interpretations have coherence, correspondence, and inclusiveness. In other words, they should hold together, relate to the work appropriately and deal with it as a whole.

Feelings are guides to interpretations. Yes—we make things with our whole selves, so it is appropriate to read them that way, too.

It is interpretively risky to arrive at a confident interpretation of one piece of art without knowledge of any others by the artist. (It seems to me that Barrett is presenting a new principle here but that it is has not been set in bold type in the article—a mistake?) I think this could be argued. Is the artist’s intent what is important? Are we to assume that the artist could not strike out on a new path or make a complete break with what has gone before?

An interpretation of an artwork need not match the artist’s intent for the artwork. No argument here: artists are not necessarily the best or most articulate interpreters of their own work and, like the rest of us, are probably not fully aware of all the influences to which they are subject.

The objects of interpretations are artworks, not artists. A valid principle, but could it conflict with Barrett’s principle about the need to take into account an artist’s broad output?

All art is in part about the world in which it emerged. Yes, but what are the limits on this? When should we start to worry that the interpreter’s knowledge of ‘culture’ might be projecting ideas and influences that simply aren’t there? And in today’s highly-mobile societies with multiple cultural influences, what is ‘the world’ in which a piece emerges? Is this ‘world’ unique to every artist, and at different times of her life?

All art is in part about other art. Some of these statements are quite sweeping and categorical. It is a valid point that “art does not emerge within an aesthetic vacuum,” but do the aesthetics in question only have to arise from the art world? It sounds strange to say that “[a]rt can be about life, about art, or both.” Where is the dividing line?

Interpretation is ultimately a communal endeavor and the community is eventually self-corrective. Barrett is right to call this “an optimistic view of the art world and scholarship”—it sounds like an article of faith to me. If the art world does not self-correct, how would we know? What would be different? How would we test the degree of correction? From what standard?

Good interpretations invite us to see for ourselves and to continue on our own. The implication here is that art and interpretation are part of an ongoing process of dialogue and perhaps education/refinement of opinion and understanding.

‘Visual Stance’ - Gaze and Glance and ‘Direct Address’

The Gaze in Portraiture

Online article by John Frederick Anderson, heavily drawn from a portion of a book by Norman Bryson (“The Gaze and the Glance” in Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze, (1982) Macmillan). The importance of different levels of looking in art, from the glance (short-lived, furtive, stolen) to the gaze (longer, open, admiring?). Cultural differences in where the gaze lands; the direct gaze as a sign of aggression in the animal kingdom. A direct gaze between humans can also be a sign of aggression, or at least confidence. Does this also mark the line between portraiture (gaze) and street photography (glance)?

Nicolas Mirzoeff (1998) Visual-Culture-Reader, Routledge, 2009 (“Introduction to Part Five,” pp.391–397).

- Feminist and queer theory have placed importance on the gaze in terms of power relationship (asserting the right to look on another), to the point of proposing that “the gaze is in itself male, objectifying and subordinating women.” (391)

Recognition that sex is not merely present in genitalia but throughout a human being.

Growth in medical/anatomical knowledge is rationalist (and somewhat mechanical)—viewed as enacting “a man’s claim to rational authority over (feminine) nature.” (392)

Life drawing not open to women; Freudian psychoanalytic view of difference between the sexes rooted in presence and absence (castration) of a penis.

Role playing of the ‘heterosexual binary’ in presenting stereotypes of masculinity and femininity, which may or may not be related to gender. (393)

What happens to the ‘heterosexual binary’ if the subject or the object of the gaze is not heterosexual? (394) → expanded set of identities and meanings

These expanded identities and meanings can be subversive of gender norms or supportive of them (what is the impact of drag? in what context? for what purpose?) (395)

Importance of viewpoint: images can pose questions of the one looking on them, just as easily as the one looking may exercise the gaze.

Interesting differences in comfort with images and gaze, depending on the viewer’s expectations and personal norms: ‘some lesbian and gay readers demand unambiguously “safe” images in the gay press whereas they revel in transgressive, contradictory and subversive pleasures in the mainstream’ (Reina Lewis, quoted on 396).

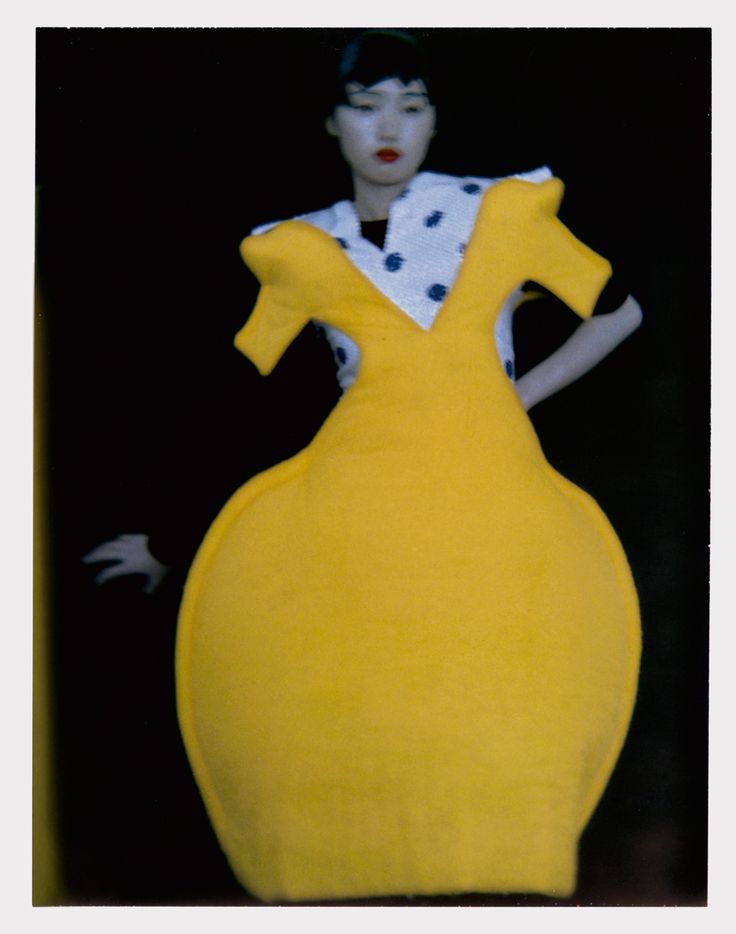

Tate Debate: When is appropriation homage and when is it plagiarism?

Appropriation has a long history in art: Pablo Picasso; Georges Braque; Kurt Schwitters; Andy Warhol. Some image appropriation is a necessity (e.g., orthodox iconography) while other uses are meant to comment or subvert the original piece. Advent of digital media has made appropriation much easier and more common. When is this a problem?