Fern Hill (1945) is a poem by Dylan Thomas, first published in the October, 1945, Horizon magazine, with its first book publication as the last poem in Deaths and Entrances. [source: Wikipedia, accessed 24 October 2016]

- What’s the mood of the poem? How does it make you feel?

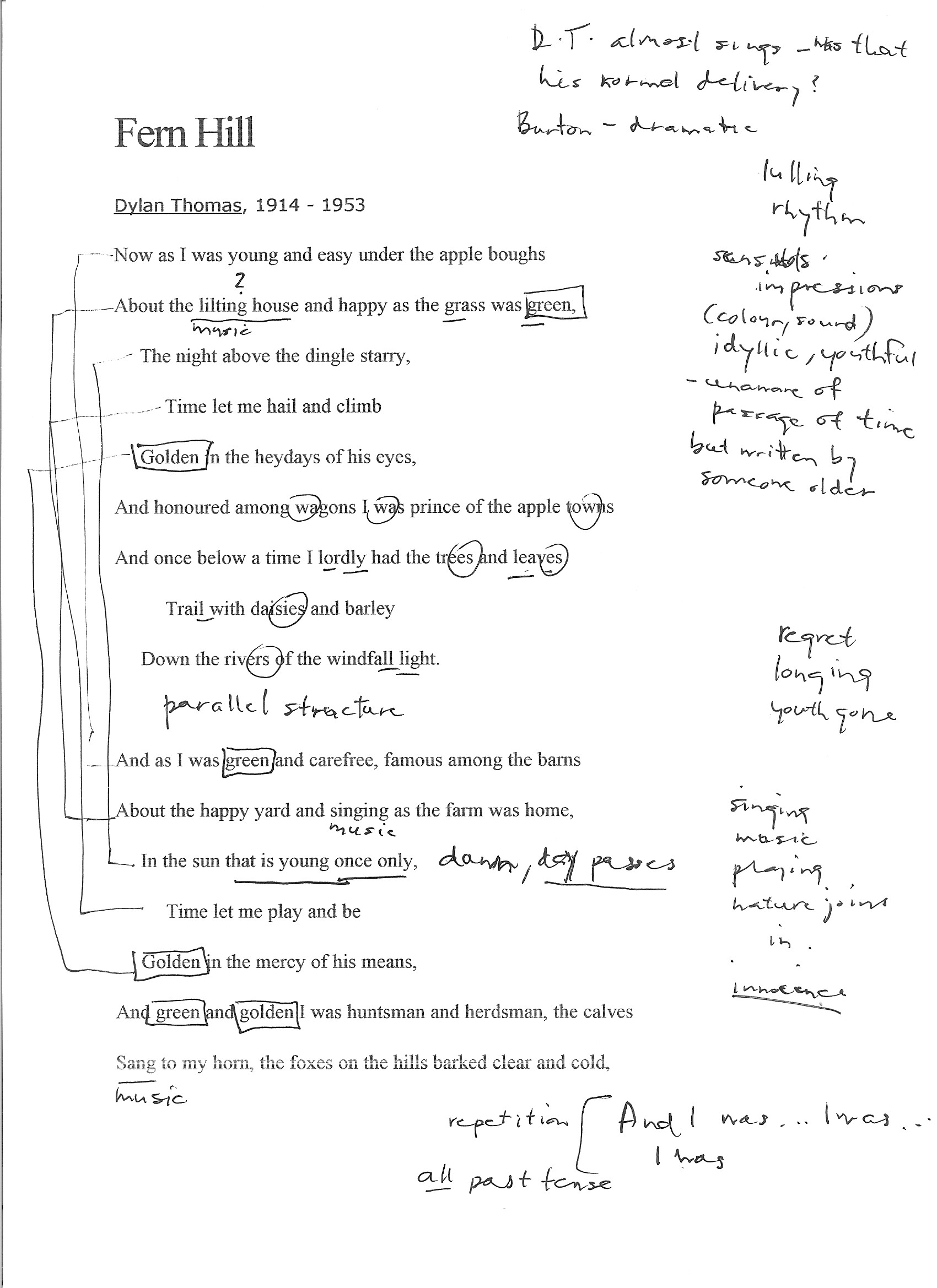

The mood of the poem seems wistful to me. Although the bulk of the text conjures up beautiful images of a blessed childhood, the way it is written in the past tense—"And I was... And as I was...I was...I was..."—leaves the clear sense that the time of youth is now gone. The piling up of sensory images, the use of colour and sound, made me feel a certain rose-coloured nostalgia. At the same time, there was a creeping awareness that although the subject has all summer to play, the poem was written by someone older who understands that childhood does not last forever ("In the sun that is young once only").

- What poetic devices does Thomas use and what effect do they have on the poem?

Thomas makes little or no use of rhyme in this poem, but he makes powerful use of several other devices:

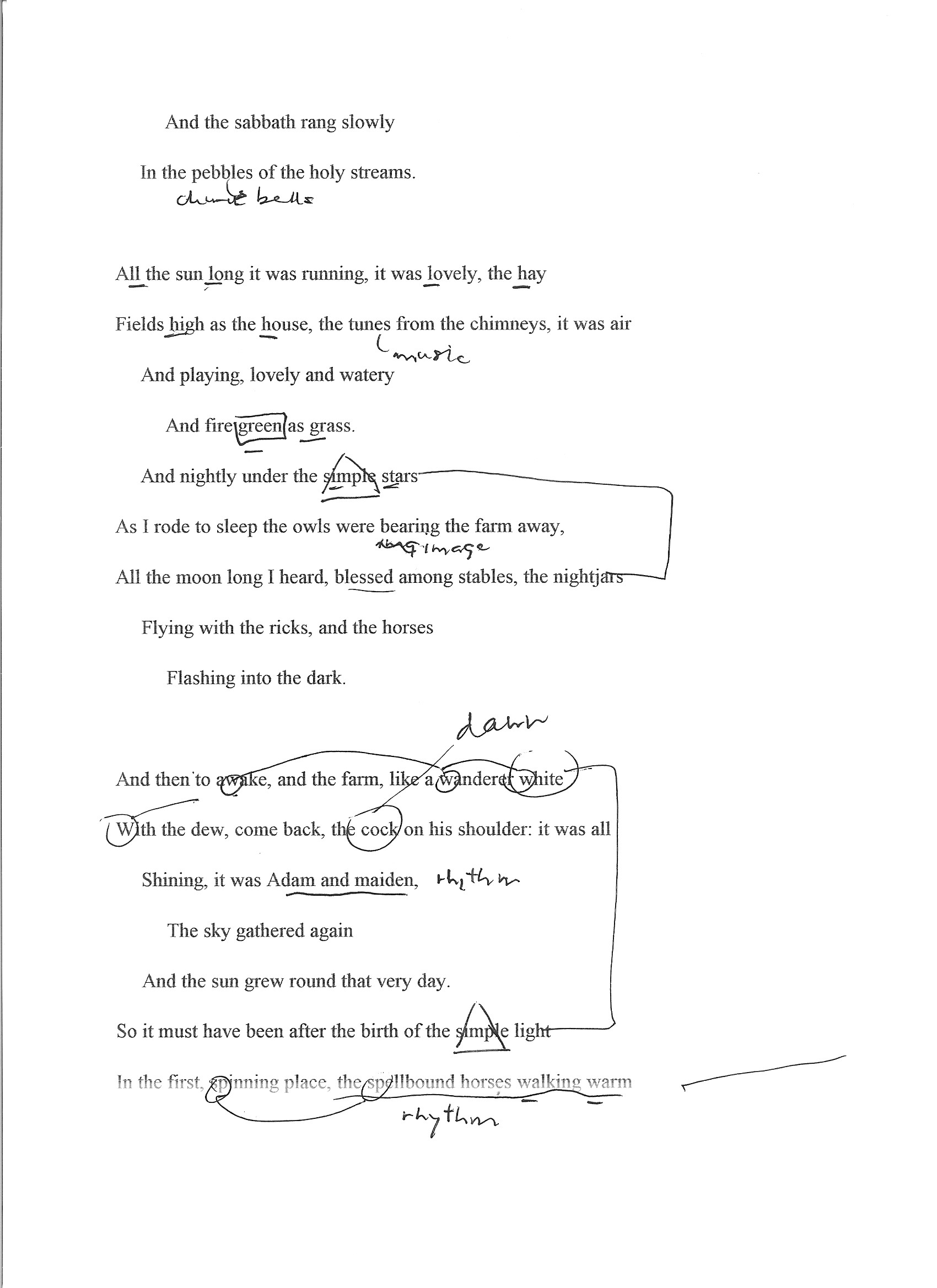

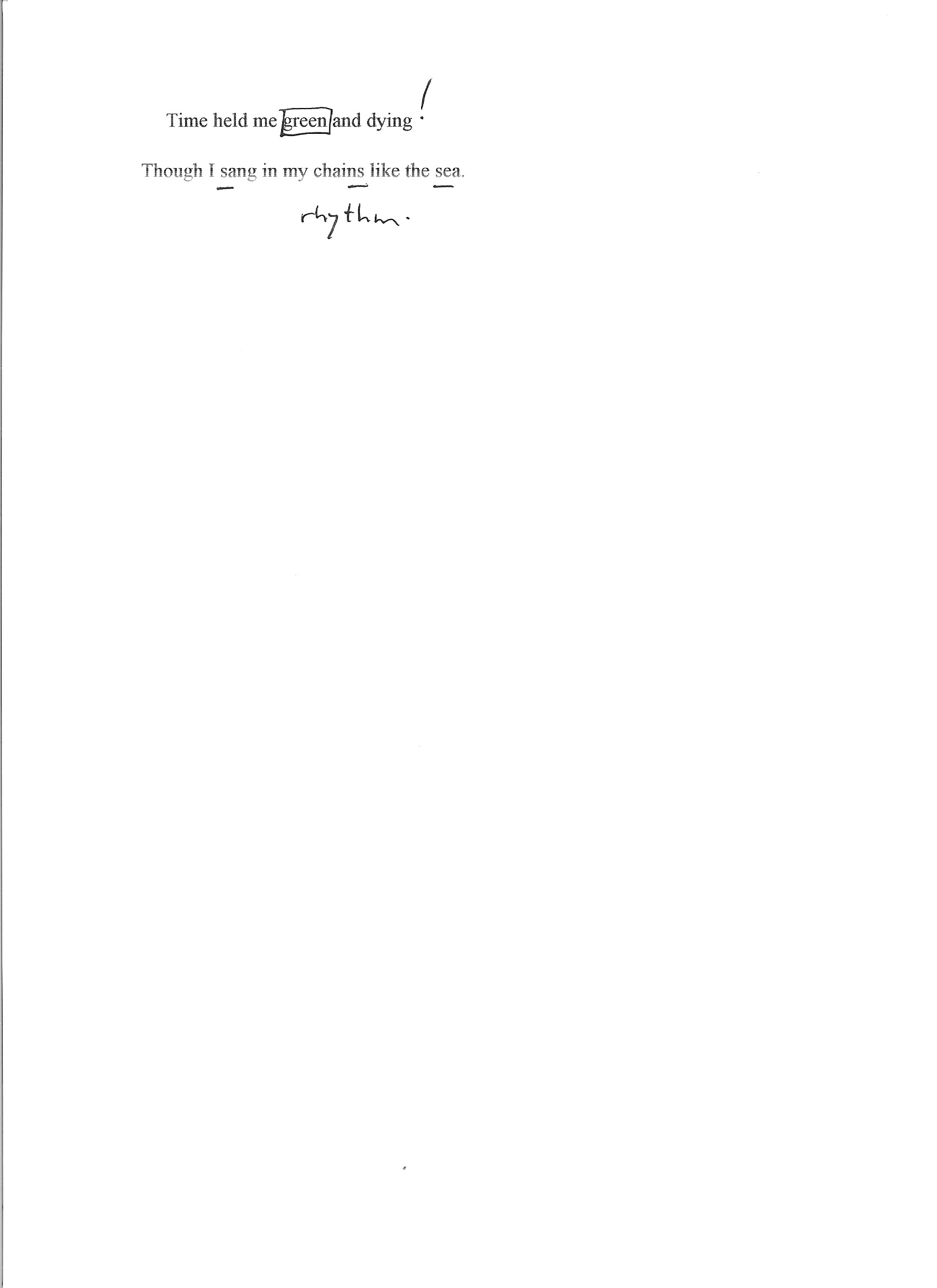

Rhythm — "the spellbound horses walking warm" — For much of the poem, the gentle rhythm carries the reader along like the boy enjoying the summer. The sharp break in rhythm in the last line is a rude awakening to the demands of time.

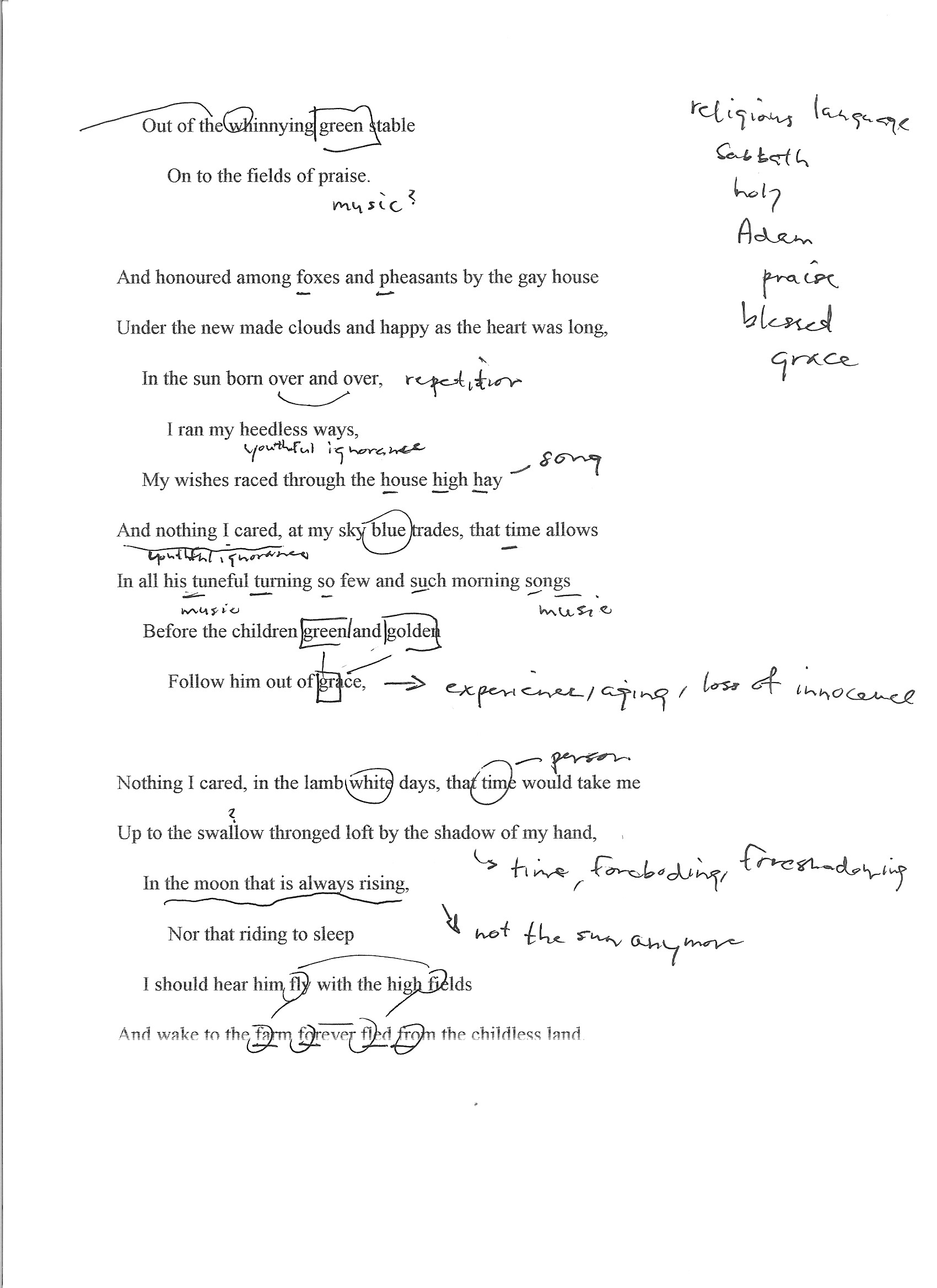

Repetition—"green," "golden," "And I was...I was..." — The use of repetition serves to heighten the effect of memory: particularly sharp impressions from the past that linger with us and trigger other memories.

Alliteration — "And wake to the farm forever fled from the childless land," "My wishes raced through the house high hay" — The alliteration briefly speeds up the rhythm of the poem and help to make us think of play or breathless speed.

Assonance — "Trail with daisies and barley" — This line may have two examples of assonance: the long "a" linking "trail" with "daisies," and the long "e" sound shared by "daisies" and "barley." They act like a kind of internal rhyme in a single line and help to move the rhythm along.

Consonance — "Shining, it was Adam and maiden" — The repetition of the "m" and "d" sounds is pleasing and helps to make the text flow by, just as time is flowing by in a carefree way.

Onomatopoeia — "Out of the whinnying green stable" — This device helps us to hear the sound in a way that goes beyond mere description: it helps us to share the experience of the boy in the poem.

Personification — "Time let me play and be / Golden in the mercy of his means" and other examples — I think that this particular use of personification helps us to feel the poet's bitterness more fully: it can be hard enough to accept aging and death as an inevitable part of life, but it seems even worse to think that there might be an intelligent figure behind it.

Simile — "and the farm, like a wanderer white / With the dew..." — The simile compels us to use our imagination to make meaning. We are not reading a news report: we have to engage with the text in a more deliberate way, with a different kind of thinking and appropriation.

Metaphor — "I was prince of the apple towns" — The boy was not a prince, but we can remember what it is like to be a child and think that we might be for a moment.

- How do the poetic devices help evoke the themes of time and place? Can you identify any other theme running through this poem?

Thomas evokes time (references to age, time of day, movement of the sun, seasons and other natural references, and use of verb tense) and place (descriptions of the farm and its natural surroundings) in fairly direct ways. Perhaps more important is the way he uses poetic devices to move beyond mundane descriptions and invite the reader to experience the time and place through the senses—the sights (frequent repetition of "green" and "golden"), sounds ("About the happy yard and singing as the farm was home"), and emotions ("About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green") of a blissful childhood.

Time and place are the backdrop where Thomas explores the universal themes of youth, its inevitable loss and mortality. At the beginning of the poem he can write that "Time let me hail and climb / Golden in the heydays of his eyes," but by its end he knows that "Time held me green and dying". The personification of Time and its possession of youth is powerful.

- What is the poem is saying about time and place (and any other theme you’ve identified)?

The poem is saying that time and place are... for a time and place. The sun and moon, the seasons of nature continue their courses but the individual human does not. We may experience them for a spell and naively believe that we are like them, but we are not: Time masters us. Youth, though enjoyable, passes for us all.

- What lines or images stay with you? What do they remind you of or how do they make you feel?

The repetition of "apples" coupled with "green" and "golden" have stayed with me—they do an excellent job of conjuring up the sense of mid- or late summer. It's not hard to imagine being a boy again, playing in the warm sun on a holiday that goes on forever. It's very appealing.

- What’s the rhythm like? Is it choppy or is it flowing and smooth? How does the rhythm impact on the poem?

The poem has a lulling rhythm, peaceful and unhurried. At times, it seems almost playful as in the line "My wishes raced through the house high hay," which sounds like it could be a child's song or the kind of wordplay that a child would enjoy. The rhythmic pattern supports well the idyllic imagery that the poet builds into a portrait of a carefree youth. The very last line of the poem shatters the reverie with a new rhythm that falls like a series of blows: "Though I sang in my chains like the sea." Childhood is over.

- Is the ‘speaker’ important? What are his views? Are they apparent or inferred?

By inference, the speaker is a young boy ("I was prince of the apple towns") raised in the countryside. We never learn his identity, but this is ultimately not very important: the poem addresses universal themes of innocence and its loss, life and death. His views become quite apparent but the reader learns them through accumulated inferences. Thomas could have said plainly, "I had no idea that childhood and its pleasures come to an end, but they did and it is a shock to face mortality." Instead, he draws the reader through an experience of youth that seems never-ending and makes them feel the loss of its passing away.

- Are there any lines you don’t get? Can you hazard a guess as to what they mean or allude to?

No, there were not. I had to read some of the lines out loud more than once to make sure I had the right rhythm, and found that helped me to understand the phrasing. I had to check the meanings of a couple of words ("dingle," "nightjars") but I did not find the poem difficult.